Incision Point

Shirley Jackson’s 1951 novel Hangsaman occupies an odd position in her substantial repertoire of novels and short

stories. On the surface, the novel functions similar to a typical all-American

bildungsroman, focusing on the interior life of a 17-year-old girl, Natalie

Waite, as she leaves home, her domineering father, emotionally vacant mother,

and her childhood, behind, and begins her studies at a small women’s college.

This surface plot quickly reveals itself to be a sort of narrative red herring:

uncanniness bleeds into the water and suddenly the reader is shoved overboard

into the deep end, something far more complex and even sinister occurring under

the guise of a standard coming-of-age story. Hangsaman is arguably the

most experimental and inchoate of Jackson’s work, and thus, frustrating for

many of its readers. The novel is perhaps Jackson’s least-discussed text, only

seriously considered by a handful of scholars thus far, and this relative

absence of criticism may draw directly from its narrative strangeness: unlike,

say, the archetypal Gothic-phantasmic vision of The Haunting of Hill House,

or the succinct, unsettling-but-clear allegory of “The Lottery,” Hangsaman is far more difficult to accurately classify or pin down.

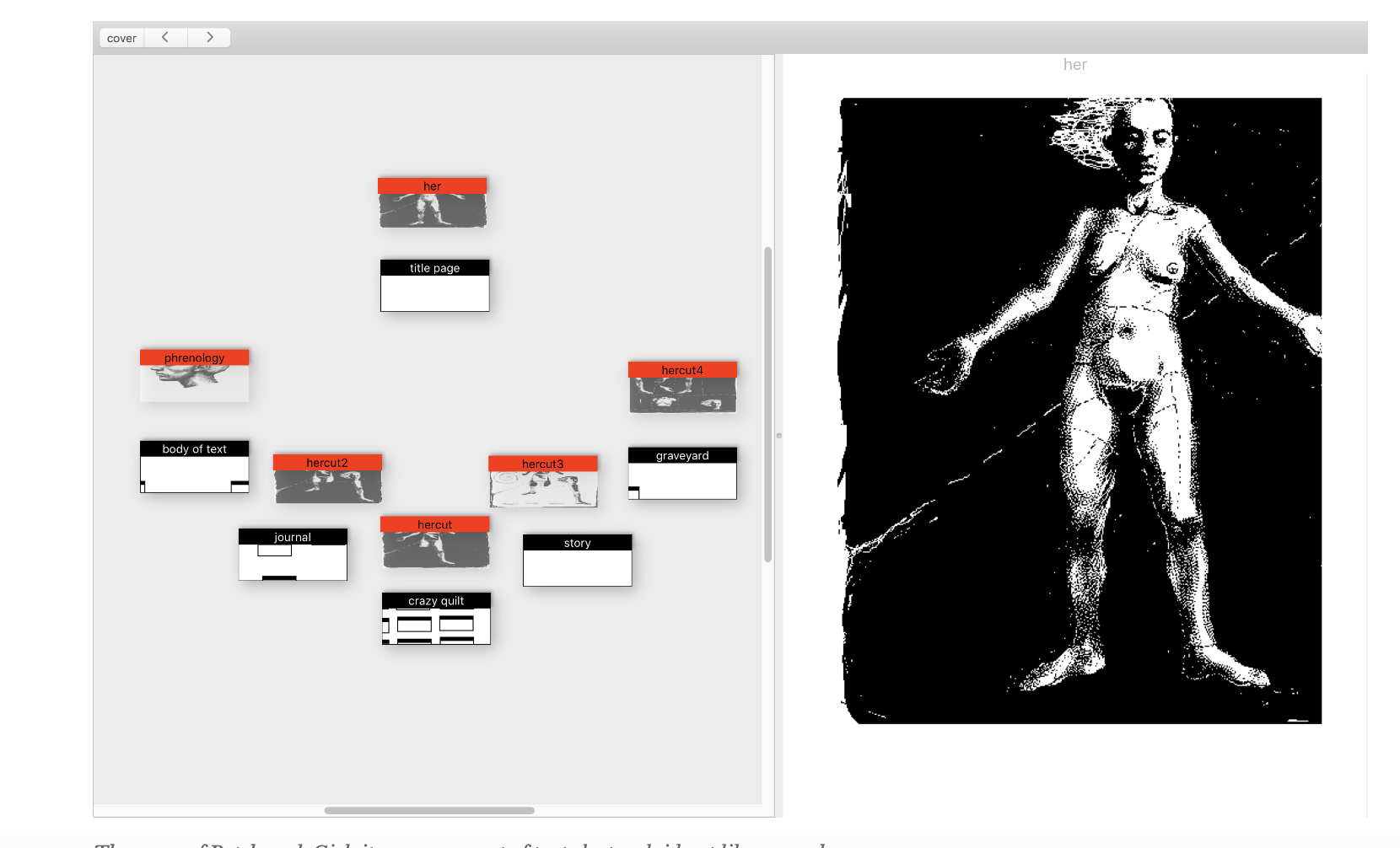

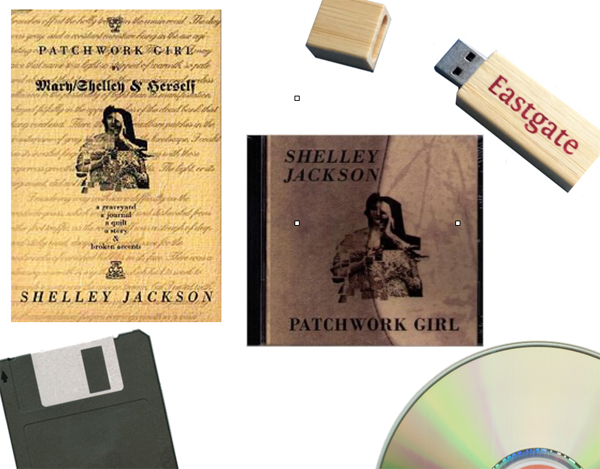

Similarly, Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl offers no seamless, easily summarized “plot.” Patchwork Girl is a 1995 hypertext novel that functions somewhat similarly to a choose-your-own-adventure story, except that this story is a queer, feminist retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein from the point of view of the monster herself. Patchwork Girl is comprised of several key components, not so much “chapters” as sections, with no designated order for the reader. Patchwork Girl is widely considered a groundbreaking experiment in hypertext narratives. As Carolina Sánchez-Palencia Carazo and Manuel Almagro Jiménez distill it in their analysis of the text, “Patchwork Girl is not simply one more text that reflects the aesthetics of fragmentation and hybridity; it is a hypertext that allows for material and technological possibilities that would be unthinkable in a printed version. As a consequence, the relationship between reader and text also becomes provisional and mutable inasmuch as different possible readings arise: one ordered, as in the chart view, and another chaotic or random-like, simply by clicking on any word in a given lexia.”[1]The format is that of Frankenstein’s monster, herself, gendered as feminine and embodied in a digital structure: the reader accesses the text through a digital software, and clicks on different “pieces” or disjointed “limbs,” all located in the semi-charted void of the “cemetery,” in order to read each section. There is no particular order offered, and, in the original version, the reader must use their cursor to “unstitch” and “restitch” the visually illustrated monster as a means of uncovering and continuing the story. Shelley Jackson explicates this narrative technique in “Stitch Bitch,” her auxiliary lecture, or de facto artist/writer’s statement, on the text:

Could this non-linear, interactive mode of storytelling offer a form of narratological fragmentation and subversion that might illuminate what is perhaps more elusive or less readily visible in Hangsaman? This essay intends to explore this possibility.

![]()

1. “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s ‘Patchwork Girl,” 2006, p.116.

Similarly, Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl offers no seamless, easily summarized “plot.” Patchwork Girl is a 1995 hypertext novel that functions somewhat similarly to a choose-your-own-adventure story, except that this story is a queer, feminist retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein from the point of view of the monster herself. Patchwork Girl is comprised of several key components, not so much “chapters” as sections, with no designated order for the reader. Patchwork Girl is widely considered a groundbreaking experiment in hypertext narratives. As Carolina Sánchez-Palencia Carazo and Manuel Almagro Jiménez distill it in their analysis of the text, “Patchwork Girl is not simply one more text that reflects the aesthetics of fragmentation and hybridity; it is a hypertext that allows for material and technological possibilities that would be unthinkable in a printed version. As a consequence, the relationship between reader and text also becomes provisional and mutable inasmuch as different possible readings arise: one ordered, as in the chart view, and another chaotic or random-like, simply by clicking on any word in a given lexia.”[1]The format is that of Frankenstein’s monster, herself, gendered as feminine and embodied in a digital structure: the reader accesses the text through a digital software, and clicks on different “pieces” or disjointed “limbs,” all located in the semi-charted void of the “cemetery,” in order to read each section. There is no particular order offered, and, in the original version, the reader must use their cursor to “unstitch” and “restitch” the visually illustrated monster as a means of uncovering and continuing the story. Shelley Jackson explicates this narrative technique in “Stitch Bitch,” her auxiliary lecture, or de facto artist/writer’s statement, on the text:

The novel has become the golem, the monster that acts like everyone else, only better, because the narrative line is wrapped like a leash around its thick neck. I would like to introduce a different kind of novel, the patchwork girl, a creature who's entirely content to be the turn of a kaleidoscope, an exquisite corpse, a field on which copulas copulate, the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on an operating table. The hypertext. (7)

Could this non-linear, interactive mode of storytelling offer a form of narratological fragmentation and subversion that might illuminate what is perhaps more elusive or less readily visible in Hangsaman? This essay intends to explore this possibility.

1. “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s ‘Patchwork Girl,” 2006, p.116.